52 Ancestors: Thomas Marion Elonzo Manning - When Family Stories Don't Match the Records

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

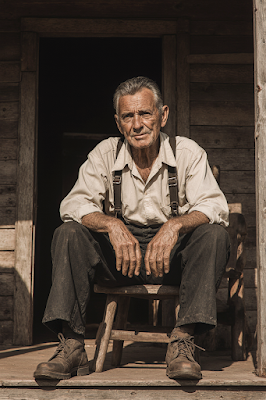

One of the most frustrating aspects of genealogy research is when family oral history directly contradicts the documentary evidence. This week's ancestor, my husband's 2x great-grandfather Thomas Marion Elonzo Manning, presents exactly this kind of puzzle—one that has me questioning everything I thought I knew about his character and his relationship with his daughter.

The Man Behind the Records

Thomas was born on November 7, 1874, in Montgomery County, Arkansas, to Ira W. Manning and Tamsey Manervia Sessions. His childhood was marked by loss—his father died around 1888 when Thomas was just 14, leaving him to help support his mother and younger siblings. After his mother remarried, Thomas gained several half-siblings through the Shopshire family.

At age 25, Thomas married 17-year-old Mattie Smith on March 24, 1900, in what was then Indian Territory (later Oklahoma). They built their life as farmers, moving around McIntosh County as Thomas sought better opportunities. The couple welcomed four children: Carl (1904), Ira Webster (1906), Henry Lee (1908), and Flora Mae (1911).

Following the Census Trail

The federal censuses paint a picture of a hardworking farmer constantly seeking stability:

- 1900: Living in Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory, newlywed farmer

- 1910: Burton, McIntosh County, Oklahoma, with Mattie and their growing family

- 1920: Hanna, McIntosh County, with new wife Martha (Mattie had died sometime after 1910)

- 1930: Dryden, Harmon County, still farming at age 55

- 1940: Martin, Harmon County, in his final recorded census

Thomas remarried after Mattie's death to Martha E. Sowells, and they had three more children: Wilson (1919), M. Lonzo (1924), and James Kenneth (1925).

The Family Story That Doesn't Add Up

For years, I've carried a story passed down through the family from "Aunt Mattie" (a family member whose exact relationship I'm still trying to pin down). According to her, Thomas and his second wife Martha disowned his daughter Flora Mae because she married a "half-breed"—their cruel term for Ernest "Joe" Connor, who was supposedly part Native American.

This story painted Thomas as a man whose racial prejudices cost him his relationship with his daughter, who died tragically young at just 28 in 1940. It was a painful family narrative that seemed to fit the harsh realities of early 20th century attitudes.

But then I found the marriage record.

When Documents Challenge Family Lore

Flora Mae was only 17 when she married Ernest Connor. In those days, a minor needed parental permission to marry. And there it was, clear as day: Thomas Marion Elonzo Manning's signature on his daughter's marriage certificate, giving his blessing for the union.

This changes everything. If Thomas truly disapproved of Ernest because of his ethnicity, why would he sign permission for his teenage daughter to marry him? The documentary evidence directly contradicts the family story I'd accepted for years.

The Mystery Deepens: Aunt Mattie's Perspective

Here's where the story becomes even more puzzling. Aunt Mattie wasn't just any family member passing along gossip—she was Flora Mae's own daughter, sister to Grandma Estelle. This means she was Thomas's granddaughter, and she was telling a story about her own grandfather supposedly disowning her own mother.

This family connection makes her account both more credible and more confusing:

- She had a personal stake in the story - This was about her own mother's treatment by her grandfather

- But she was likely very young when these events occurred (Flora Mae died in 1940 when Mattie would have been a child)

- She might have heard the story secondhand from her father Ernest or other family members

- The story could reflect Ernest's perception of how he was treated, rather than objective reality

- There might have been later family conflicts that got projected back onto earlier events

The Genealogist's Dilemma

This is exactly the kind of situation that makes genealogy both fascinating and frustrating. We want to tell our ancestors' stories accurately, but how do we handle it when the "known" family history doesn't match the records?

Do we:

- Trust the documents over oral history?

- Assume there's more to the story that we haven't uncovered yet?

- Accept that family stories sometimes become distorted over generations?

- Keep digging until we find the truth?

In Thomas's case, I'm inclined to believe the marriage certificate. Legal documents created at the time of events tend to be more reliable than stories passed down through multiple generations. But I'm not ready to completely dismiss Aunt Mattie's account either—there might be kernels of truth buried within it.

Possible Explanations

Knowing that Aunt Mattie was Flora Mae's daughter opens up several possibilities:

The child's perspective: Mattie might have grown up hearing her father Ernest talk about feeling unwelcome or discriminated against by Thomas's family, without understanding the full context or timeline.

Later family dynamics: Perhaps Thomas initially accepted the marriage (hence signing the certificate) but relationships soured later due to personality conflicts, financial disputes, or other family drama that had nothing to do with race.

Protective storytelling: Ernest might have told his children a simplified version of family tensions to explain why they didn't have close relationships with Thomas's side of the family.

Mixed messages: It's possible Thomas signed the certificate reluctantly or under pressure, and his true feelings came out in his behavior afterward.

What This Means for Thomas's Story

The marriage certificate suggests that Thomas wasn't the outright bigot that family lore painted him to be—at least not initially. He gave legal permission for his teenage daughter to marry Ernest, which indicates some level of acceptance of the union.

But Mattie's story as Flora Mae's daughter can't be dismissed either. She was sharing what she understood to be her family's history, and her perspective as the child of that marriage gives her account particular weight.

The truth probably lies somewhere in the middle—perhaps in the complex dynamics of blended families, economic pressures, and the everyday conflicts that can strain relationships over time.

The Ongoing Investigation

Thomas died on December 2, 1941, at age 67 in Oklahoma, buried in Fletcher Cemetery in Comanche County. Flora Mae had died the year before, in 1940, far too young. Whether father and daughter had a close relationship or were estranged for reasons having nothing to do with racial prejudice, I may never know.

But I'll keep digging. Somewhere in the records—perhaps in letters, probate documents, or other family members' stories—there might be clues that help reconcile Aunt Mattie's account with the documentary evidence.

Lessons Learned

This experience has reminded me why it's so important to:

- Document sources carefully - Who told the story, when, and in what context?

- Verify family stories with records whenever possible

- Keep an open mind about revising our understanding as new evidence emerges

- Be cautious about making character judgments based solely on oral history

Thomas Marion Elonzo Manning's story is still being written, at least in my understanding of it. And that's okay. Sometimes the most honest thing we can say about our ancestors is that we're still trying to figure them out.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment